|

| |

Relocation Camps in World

War II

Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7th, 1941. On the following day, America declared

war on Japan. However, fighting with Japan presented worries for many Americans of

non-Japanese ancestry. They feared that the

Japanese-Americans would help Japan in the war. These fears were very ill-founded, almost

to the point of being comical. For example, some people thought that the

Japanese-Americans would grow strawberry field in a way to make a giant arrow.

This arrow would be visible by

Japanese planes, and would direct them to such important locations as power stations and

government buildings. Not one Japanese plane made successfully made it to American in

actuality.

The non-Japanese Americans saw only

conspiracy in the Issei and Nisei, a conspiracy based on racial prejudice.

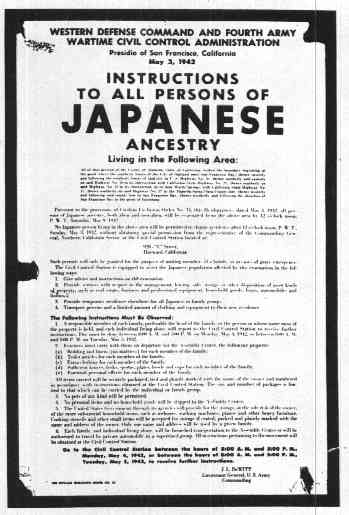

As a result of some people's fears, the FBI and local authorities began detaining Issei

leaders of the Japanese-American communities in Hawai'i and the mainland.

No formal charges were made, and there was

no due process of law. The critical point came when President Roosevelt signed Executive

Order 9066.

@

This allowed the military to remove any group from an area

without a reason. Executive Order 9066 provided the legal authority for the mass

imprisonment of Japanese-Americans.

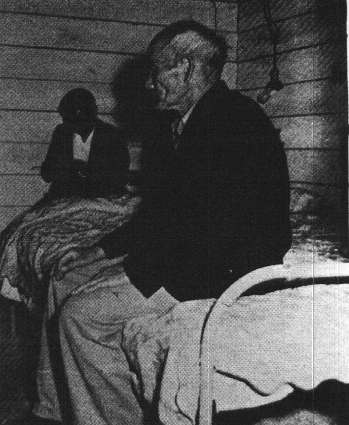

Although there were some willful reallocations, the vast majority of people were

forced into Concentration Camps (now refereed to as Relocation Camps.)

Not only was this a violation of civil rights, but they were forced to sell their

property (at just a fraction of it worth), and most importantly they were robbed of their

dignity.

@

Still, most Japanese-Americans went peacefully to prove

their devotion to America.

The Japanese-Americans on Terminal Island near Los Angeles were ordered to leave

their homes on February 25, 1942. By April, Civilian Exclusion Orders became common, and

Japanese-Americans up and down the West Coast were herded into Assembly centers.

@

@

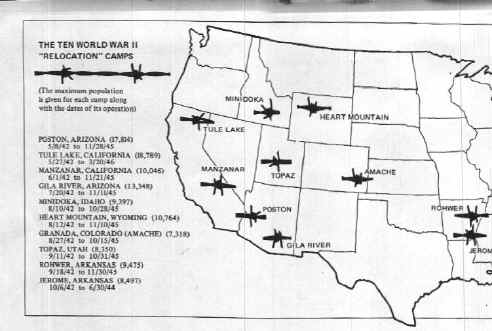

Here they were detained until taken to one of ten Concentration Camps:

Gila River (Arizona)

Poston (Arizona)

Jerome (Arkansas)

Rohwer (Arkansas)

Manzanar (California)

Tule Lake (California)

Amache (Colorado)

Minidoka (Idaho)

Topaz (Utah)

Heart Mountain (Wyoming.)

A total of 110,000 persons of

Japanese ancestry (70,000 of whom were native-born American citizens) were incarcerated

and forced into Concentration Camps. More than 2,200 ethnic Japanese in 13 Latin American

countries were taken from their homes and put into camps as well.

It is

ironic that the Japanese-Americans were incarcerated because the government feared they

were loyal to Japan, but they submitted to the indignity because they were loyal to

America.

It is

ironic that the Japanese-Americans were incarcerated because the government feared they

were loyal to Japan, but they submitted to the indignity because they were loyal to

America.

These camps were under the authority

of the War Relocation Authority (WRA.) Even though the WRA tried to make the camps seem

like normal life, guard towers, barbed wire, and inhospitable locations such as deserts

and swamps made the camps unpleasant. They were overcrowded and detestable.

In Hawaii, however, the Japanese-Americans

could not be put in Concentration Camps. Most of the statefs economy depended on them.

Curfew laws were created, and several leaders were incarcerated, but their treatment was

much better than on the mainland.

President Truman signs the Japanese

American Evacuation Claims Act on July 2, 1948. This was designed to compensate

Japanese-Americans for economic losses due to forced evacuations.

Although $38 million was to be paid, very little of it

actually reached the victims. Not until President Regan signed HR 442 was there any

serious compensation.

A fund was established to pay $20,000 to Japanese-Americans

who were forced into camps or had property seized. The Latin Americans of Japanese were

not compensated until 1999. Only 375 to 400 former internees will receive the $5,000.

Though very few people fell that the money justifies what

happened, most find these settlements acceptable. gYou canft relive the life again, so

you have to go on,h said Kazuo Matsubayahi, a former internee, now 62.

Japanese-Americans for economic losses due to forced

evacuations. Although $38 million was to be paid, very little of it actually reached the

victims. Not until President Regan signed HR 442 was there any serious compensation.

D.R. |

@

@

@

@

@

|

![]()